Printing

Lithography

In 1798, Czech inventor and artist Alois Senefelder invented the reproduction process of lithography. As a result of his experiments with calcium carbonate and greasy ink, he devised a method of producing multiple copies of his artwork and writings.

Senefelder also discovered an important benefit of lithography, whereby images printed on paper could be transferred to another stone, preserving the original stone. This paved the way for ganging up multiple images for printing.

The printing process

Queensland began using the lithographic printing process to print maps in the 1860s.

The process involved the following steps:

- a map was compiled by a cartographic draftsman

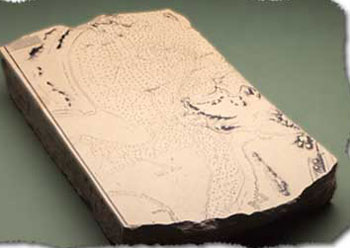

- specialist lithographers transferred the map to a printing stone (limestone specially imported from Bavaria)

- detail was traced in reverse onto the stone using greasy ink

- lithographs were printed from this stone at a production rate of 300 copies per hour.

Build-up of ink caused the work on the stone to fatten after being used as a print master. This consequently made the original unsuitable for further reproduction. Before the original was disposed of, the stone was inked and a paper copy pulled. Whilst the ink was still wet on the paper, it was dusted with a fine red powder, known as raddle or dragon's blood. The powdered copy was very carefully placed on a new stone and was then run through the press, leaving a powdered impression on the stone. The edges of the sheet were glued in position around the stone. Small sections of a protective paper cover were gently raised to allow redrawing of the work without disruption to the remainder of the powdered image.

Production of a coloured map containing (e.g. 5 colours) would require the preparation of 5 such separate powdered impressions.

The stones were heavy and fragile. It was important that they were perfectly aligned with the paper to retain information integrity. The final output quality and texture was exquisite.

To prolong the useful life of the originals, the process was modified. A copy of the original was taken and was then transferred directly to another stone from which the printing was done.

Advancements in printing processes

Towards the end of World War I, great advances were made in map reproduction. The destruction of a large number of the Bavarian limestone quarries during World War I formed the catalyst for the replacement of stone plates with zinc and aluminium plates.

The process of printing from stone continued in Queensland until the 1930s when zinc plate printing was introduced. This resulted in a saving in process time and improved accuracy in the scale of the lithographs.

Offset lithography

It was toward the end of the 1950s and into the early 1960s that the process of offset lithography became popular with printers. Offset lithography was an extended technology of lithography from stone.

As with lithography, the general principles of this process work on the foundation that water and oil repel each other. Secondly, the ink is offset from the plate to a rubber blanket and then from the blanket to the paper.

The offset machine consists of three main cylinders. The first holds the alloy plate containing the image, whilst a rubber blanket is fastened to the second cylinder.

The image is transferred from this blanket to the third cylinder carrying the paper. This last cylinder is known as the impression cylinder.

The printing plate's image area is chemically treated to make it oil receptive and therefore water repellent, while the non-image areas are water receptive and ink repellent.

Related links

- Learn about Queensland’s mapping history.

- View images of instruments and equipment used to survey and map Queensland.