Liver Transplant Evaluation and Assessment Guide

The liver transplant operation

Liver transplantation is considered to be the most difficult of all transplants. The surgery takes between 4 and 12 hours.

It happens in two parts

- The removal of your liver, a Hepatectomy or Explant

- Sewing in the donor liver, the transplant

Step 1: Removing your liver

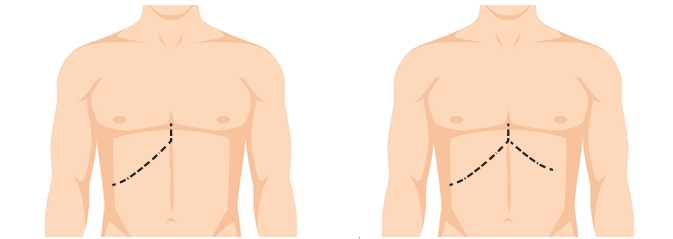

The operation will begin with the surgeon making a large cut on your upper abdomen. This might be on the right side – called a Hockey Stick or cover both sides of your belly – called a Mercedes Benz incision. See Figure 1

If you have a lot of fluid, or ascites, in your tummy, it will all be removed by suckers. This fluid may accumulate again after the transplant. Because the liver is high up under the ribs on the right side, an elaborate metal frame, or a retractor, is used to pull the ribs up so the team can work.

When everything is set up and the view is optimal, the next task is to cut out your failing liver. This is all about setting up your blood vessels to join the new liver to them. Getting the old liver out can be the most demanding part of the operation. The massive varicose veins that surround the liver and coat every surface of the abdomen can bleed with the slightest touch. Because the old liver does not make clot well, this is the phase of the operation where the most blood can be lost.

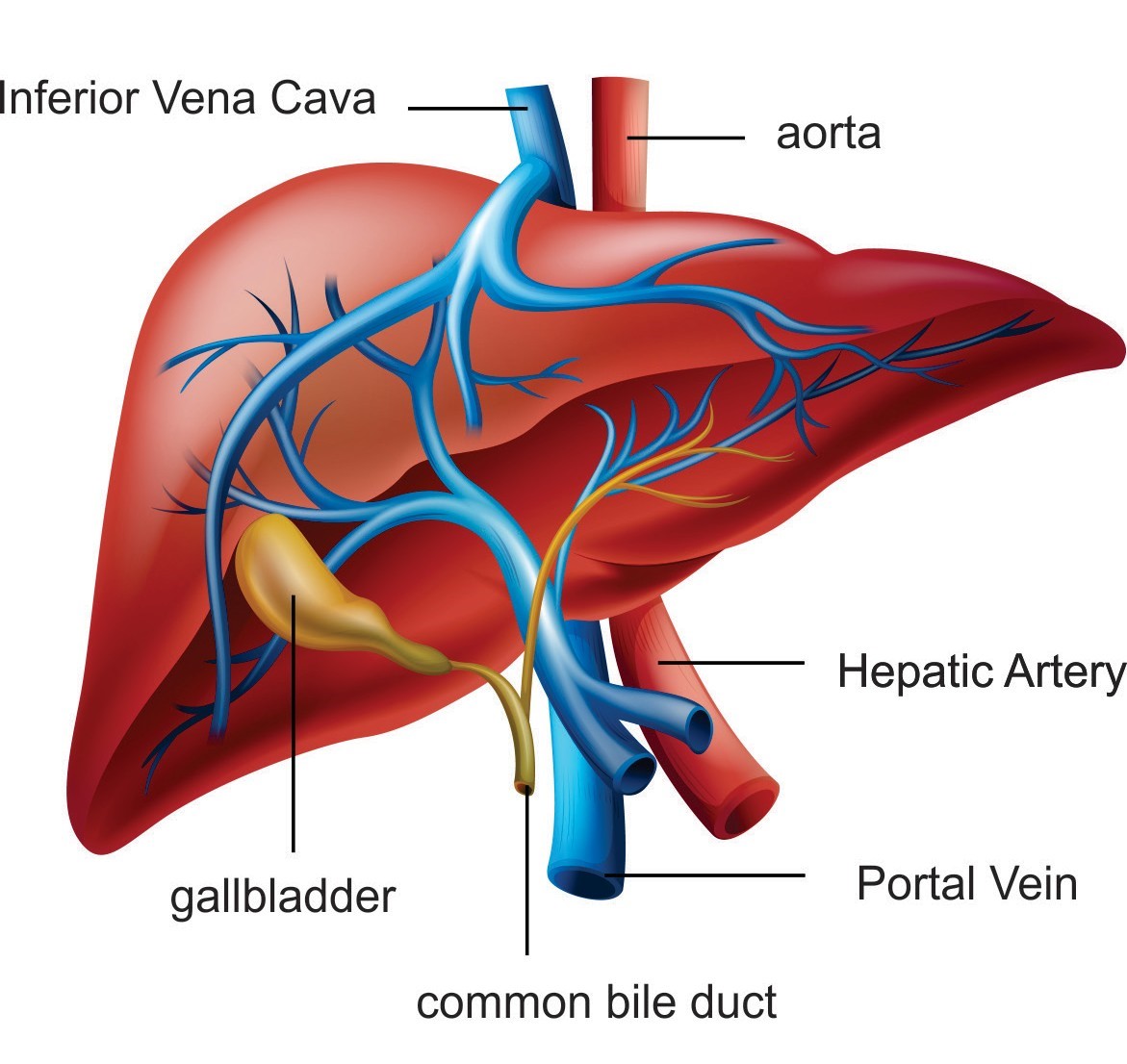

The liver must be freed from all its attachments. To understand this better, a quick lesson in liver anatomy is needed. For such a big organ, about 1 and a half kg, depending on the size of the person, the liver has very little in the way of attachments to the body. Aside from a few flimsy ligaments, the only things that really hold it in place are its blood vessels. The liver is unique because it has two separate blood supplies. Figure 2

The first is the hepatic artery that brings blood with oxygen, straight from the lungs via the heart. The bile ducts are the main beneficiary of this blood and it is for this reason that the hepatic artery is the Achilles heel of liver transplantation. If the blood stops flowing in the hepatic artery at any point after the surgery, very few livers will survive. The fragile bile ducts will die and liquefy forming lakes of bile within the liver. These pools will become infected and it is likely that you will need to be re-transplanted. This can happen at any time in your life but the risk is highest in the first few weeks after transplant.

The second blood supply to the liver is the impressive but delicate portal vein. The size of a garden hose, the portal vein drains blood from the bowels, stomach and spleen. It gives the liver cells the first pickings of the nutrients, fats and toxins produced by the gut. But the only things that really hold the liver in place are the imposing hepatic veins. Like everything in surgery, what goes in must come out and the hepatic veins are how the blood flows out of the liver. These are the 3 stout tributaries that return the blood from the liver almost directly into the heart. These hepatic veins are the most significant support structures for the liver and incredibly, only a single row of tiny stitches between these veins are all that is required to keep the new liver in place.

The Back Table

While the surgeon is working to remove your liver, another surgeon is preparing the donor liver in a process called “The Back Table”. This is where the unnecessary tissue is stripped off the blood vessels going to the liver in order to gain as much length as possible. The liver is kept in a bath of ice-cold solution while this is done.

Step 2: Sewing in the donor liver

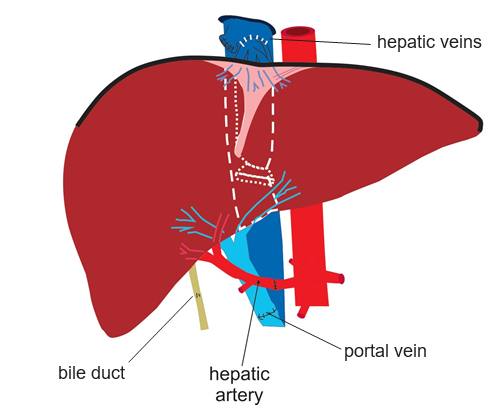

When everything is ready, the blood vessels in and out of the liver are clamped and your old liver is removed. We must work very quickly to sew the new liver in so your blood can start flowing through it. The liver is “Piggybacked” onto the blood vessel that brings blood back from your lower body to your heart. This takes about 30 minutes. See Figure 3

The new liver is taken out of the cooler and brought onto the operating table. Ice cold salty water is hooked up to a tube in the portal vein of the new liver and poured through at full speed to keep the liver cool and to flush out all the preservation fluid.

The first join up, or anastomosis, is the hepatic veins. The portal vein is next. This will bring most of the blood into the liver. It is relatively easy to twist this vein or make it too long, so a great deal of judgment must be used to cut it to just the right length. When these two join ups are complete, it is time to release the clamps and let blood into the new liver.

The cold liver once again becomes warm as the blood rushes in and returns it to its familiar rich, red colour. The liver will swell, becoming about 30 per cent bigger, expanding to fill the space where the old one used to be. This is the point where you hope the size match between the donor and recipient has been estimated correctly. If the liver is too big, it will bulge out of the abdomen making it very difficult to look for bleeding behind the liver. If it is too small, it may not be enough to function.

In the moments after blood rushes through the new liver, it is a very dangerous time. Your blood pressure may become unstable as the toxins that have built up in the bowels are released into the circulation and there is a second wave of bleeding. This is the time during the transplant that you are at highest risk of dying. The new liver takes some time to start working and the blood, still affected by the ravages of cirrhosis will take a while to clot. Little holes in all the blood vessels begin to open up one after another with the changes in pressure and each one needs to be attended to with fast precise stitches.

Once the bleeding has settled down, attention turns to the hepatic artery. Now, the pace of the operation slows down a lot. Joining this artery together is a painstaking job that must be

performed with technical perfection. About this time the liver will be starting to work a little. Clots are produced and slowly the bleeding will ease.

The final step in the operation is to remove the donor gallbladder and then join up the bile duct. Most livers will start to produce bile straight away.

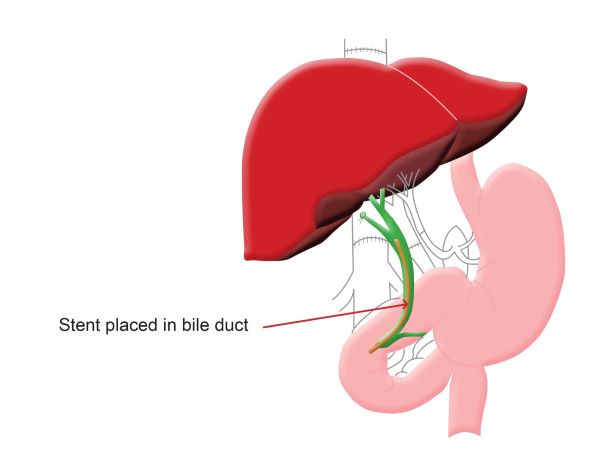

There are 2 ways to hook up the bile duct

- Duct to duct (Figure 4): Your bile duct is joined directly to the donor bile duct. Sometimes a piece of plastic tubing or a stent is placed inside your bile duct during this process. 80 per cent of patients will pass this stent into the toilet with their bowel motion and the other 20 per cent will need it removed after the transplant. This is done via an endoscopy.

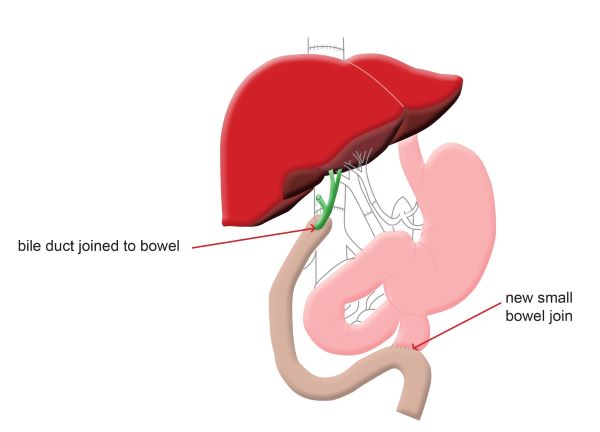

- Roux-en-Y, pronounced Roo-on-why (Figure 5): This is done for patients with diseases of their bile ducts or when there is a large difference between the size of your bile duct and the donor. The donor bile duct is sewn onto a section of your small bowel.

After completion of the bile duct connection, several large drain tubes are placed around the liver to drain away the fluid and blood. The abdominal wall and skin are closed and you will be moved to the intensive care unit.

Variations in the liver transplant operation

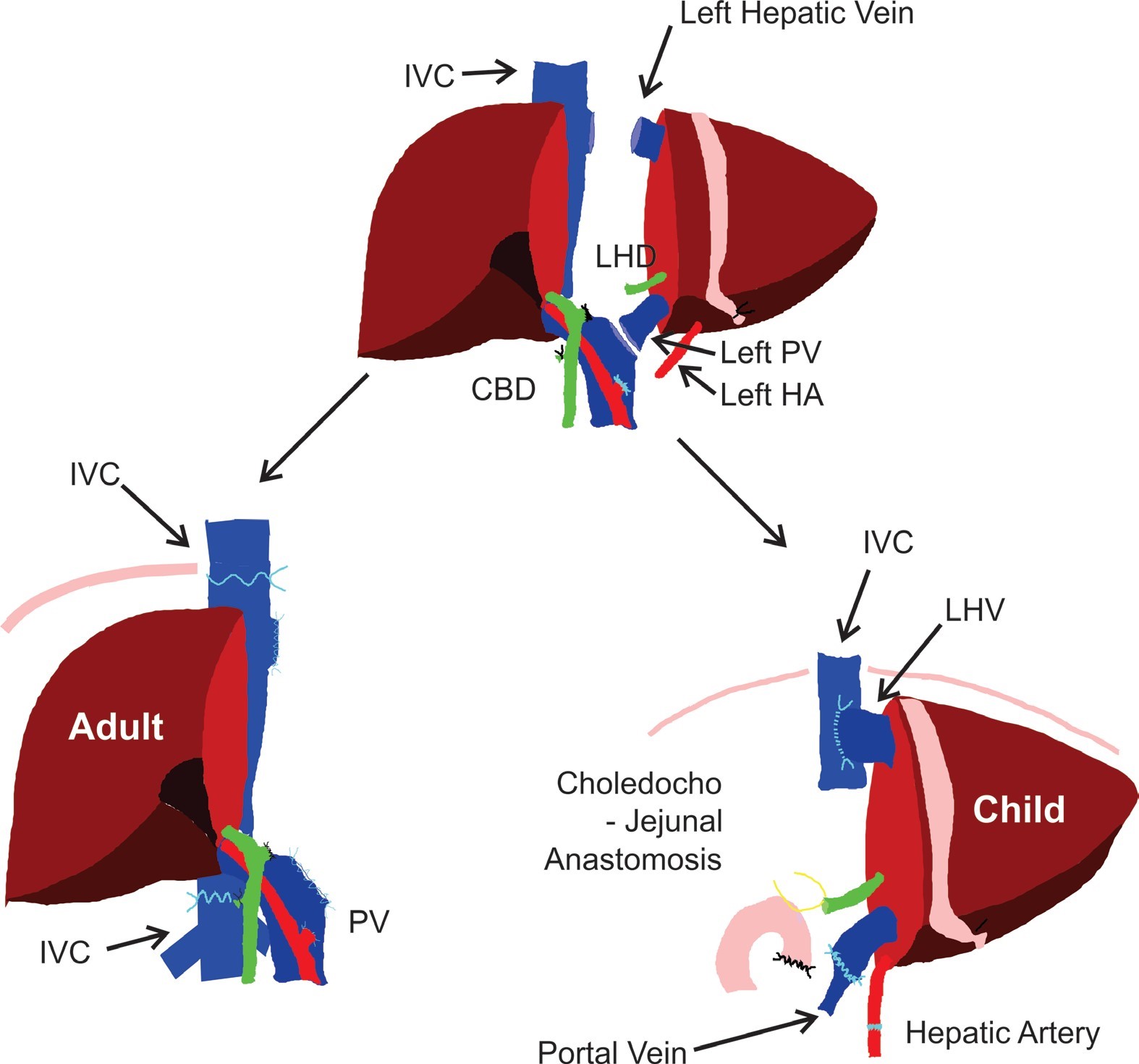

“Split” Liver Transplantation

Many patients will receive a whole donor liver. Because children having a transplant need a very small piece of liver, we will sometimes split a liver in half. The left side will be given to a child and we will use the right side for an adult. This is a good way to make the most out of a very precious thing. This is called Split liver transplant. Figure 6

This technique was developed in Brisbane and is now used around the world. The liver tissue, blood vessels and bile ducts need to be divided, increasing the possibility of bleeding and bile duct problems after surgery.

Organox

The Queensland liver transplant service will sometimes place the donor liver on a machine called Organox before transplant. This machine passes blood and nutrients through the liver. For many reasons, there are some donor livers that may not work well. This can be very difficult to figure out.

This machine will tell us with some certainty, whether the liver will function well after transplant. If the liver works well on this machine, it is likely to work well in you. You will be told if we are going to use this machine for your liver. This machine lets us use many livers that may have not been used in the past.

In this guide:

- Information and contact details for the liver transplant hepatology team

- The liver - its function and anatomy

- Signs of liver disease

- Pre-transplant assessment and evaluation

- The assessment team

- Allied Health Services

- Palliative care

- Pharmacy—medications before your transplant

- Case discussion and assessment presentation

- Will I make the list?

- The liver transplant waiting list

- Model for End stage Liver Disease (MELD)

- Support Through Education Program (STEP)

- The Donor

- What happens when you are notified that a donor liver is available?

- The liver transplant operation

- Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patient information

- The recovery period

- Pharmacy—medications after your transplant

- Rejection

- Donor family correspondence and information

- Glossary

- Previous ( https://www.qld.gov.au/health/services/specialists/queensland-liver-transplant-service/liver-transplant-evaluation-and-assessment-guide/what-happens-when-you-are-notified-that-a-donor-liver-is-available )

- Next ( https://www.qld.gov.au/health/services/specialists/queensland-liver-transplant-service/liver-transplant-evaluation-and-assessment-guide/intensive-care-unit-icu-patient-information )