Measuring distances

A number of tools were used over time to measure distances for surveys.

To ensure the accuracy and precision of the measurement, standards were introduced against which measuring tools were required to be regularly calibrated.

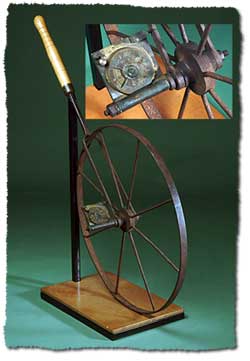

Perambulator

From the 1840s to the 1880s, the perambulator or surveyor's wheel was used to measure the distances on surveys, of features such as rivers and ranges. It was also used for road traverses and surveys of runs (pastoral holdings) where less accuracy was required.

‘The wheel and compass method of defining boundaries was quick and fairly accurate – quite accurate enough for all practical purposes where land was to be had in almost unlimited quantities, and at very low rentals. Frequently – on those far-reaching plains – we have measured from 12 to 15 miles a day, but our progress often received a check by large belts of mulga or gidya scrub, or tracks of spinifex desert. The rate of pay was £1 per mile, which taking everything into consideration, was not munificent (sic).’ (Palmer, JE 1923, 'Memories of the Never Never' Queensland Surveyor, vol. 6 no. 23, p. 8.)

Surveyors used the term 'wheeled' to denote the distance measured.

When using the perambulator over different types of terrain, varying corrections to the measured distances were made. Surveyor JR Atkinson, while carrying out river traverses on the Cressbrook Run in 1869, gave the following list of corrections he applied to his wheeled distances.

- 1 link in a chain: undulating land

- 2 links in a chain: long grass and river bottoms

- 2 links in a chain: moderate hills, ridges under 10º

- 3 links in a chain: moderate hills, ridges under 15º

- 7 links to a chain: very steep, say 20º.

The perambulator was prone to inaccuracies and surveyors took extra care when they used their wheel. GC Watson, while surveying western Queensland runs in the 1880s, described his precautions:

‘The perambulator, it may be mentioned, was very trustworthy, so long as it was well watched in the movement of the indices, which comprised two plates that were moved by an endless screw, but it was necessary to watch the movements lest any of the connecting screws should work loose or be turned too tight; or any grit interfere with the even revolution of the mechanism, which was on the principle of a patent log, for, being worked on land through mud, dust or sand, it required close scrutiny. I found that by covering the wheel with green hide, undue oscillation was prevented, and training my men to count their steps and watch the index, any irregularity would be at once detected, it being my system to record every ten chains shown by the index. My practice was to ride ahead in the line of survey, and as I kept count I would know the whereabouts of the successive ten chains, where I awaited the wheelman calling out his tally.’ (Watson, GC 1880, Building the Commonwealth: Experiences of forty years service in the civil service of Queensland, John Oxley Library Typescript)

By the turn of the nineteenth century, the perambulator was generally replaced by the surveyors' steel tape.

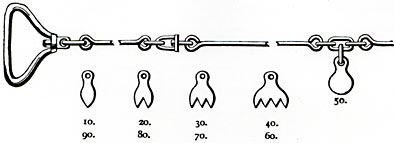

Gunter's chain

From 1839 to 1880, land surveyors in the colony of Queensland used the Gunter's chain to measure the boundaries of town allotments and country selections (farms).

Some Queensland surveyors often kept the Gunter's chain one link too long by the insertion of an extra link into the chain because land owners preferred to have excess distance rather than a shortage on their boundaries.

A Gunter's chain was very prone to inaccuracies as CW Adams, Chief Surveyor, Dunedin, New Zealand described in an article on the measurement of distances with long steel tapes in May 1887:

‘The old surveying chain, made of iron or steel wire with its hundred links, and two or three hundred small connecting rings, could hardly be called an “instrument of precision”. Its weight varied from three to six pounds and upwards, making it very difficult to avoid error through the 'sag' of the chain when measuring over uneven ground. When measuring on an incline, it was often the practice to make the measurement in “steps”, holding a part of the chain horizontal each time, but it was not desirable to take more than 30 links or so at a time in this manner, unless another assistant supported the chain midway. This chain required frequent correction, as it was always lengthening through the links and rings becoming worn. This correction was generally performed by taking out one or more of the little rings, but the chain was generally kept an inch or so long, to allow for errors caused by sagging, etc.’ (Adams, CW 1887, Trig Letters)

The use of Gunter’s chains on surveys for the Lands Department in Queensland ceased in 1880. A circular to all surveyors (staff, contract and licensed) working for the department was issued in 1880:

‘On and after the first day of January, 1880, all lineal measurements unless otherwise directed, are to be made with the broad flat band steel tape, maintained to the Brisbane Standard.’ (Queensland State Archives 1880, Circular 1880)

Steel tape

Steel tapes replaced Gunter’s chains for measuring distances.

The first flat steel tape used in Queensland was by staff surveyor A McDowall who brought one back from Sydney in 1877. In a letter to the president of the Queensland Institute of Surveyors, dated 2 April 1877, he described its advantages over the old Gunter’s chain:

‘I shall be glad if you will exhibit the steel measuring tape I have brought from Sydney ... It is made of one continuous piece of steel tape ... the links are marked by a small brass rivet, and at each ten links the numbers are marked in plain figures on each side from each end on small pieces of copper riveted to the tape ... When not in use the tape may be wound up on a light steel frame, making it a convenient parcel to carry ... It has the advantage of being in one piece (except at the handles) and will bear a tension of about 30 pounds without stretching more than 1/20th of an inch. It can, on account of its lightness, be stretched straight and is easily held in a horizontal position in measuring up or down hills or over uneven ground. These tapes appear to be coming into general use for surveying in New South Wales, and those surveyors who once use them do not appear in any instance that I could hear of, to care about using a chain again. The price is 35/-. I am now getting a steel tape made in Sydney which I propose keeping as a standard ... I think it would be advisable to recommend the surveyors who are members of the Institute to provide themselves with similar standards.’ (Queensland Institute of Surveyors Archives, Letter, 2 April 1877)

Variations on the 1 chain to 5 chain steel tapes were used for distance measurement in Queensland up until the 1980s, when they were replaced by electronic distance measuring equipment which uses light (laser) beams or radio frequencies to measure distances.

Distance measurement standardisation

The act of surveying requires distances to be measured with a high degree of precision. In order for surveyors to achieve this, their chains and tapes needed to be compared against an accurate standard. This was necessary because the chains and tapes used in the field could change their length due to wear as well as shrink or expand due to variations in temperature at the time the survey was being conducted.

Over the years a number of standards were introduced, some proving more successful than others.

In 1883 WA Tully, the Queensland Surveyor General, received from his counterpart in New South Wales, PFB Adams, a standard steel bar and associated apparatus to calibrate the department’s measuring tapes as well as those belonging to private surveyors. One task for the department’s tapes was to measure a base line on the Prairie Plain (Jondaryan) where it was critical that their exact length be known. Tully, in his annual report for 1883, described the octagonal bar:

‘In order to establish a reliable unit of measurement, I obtained from the Survey Department of New South Wales, a standard steel bar floating in mercury ten feet in length, and also an apparatus with micrometer microscopes attached, by which a steel tape of any length could be measured off direct from the bar.’ (Survey Office 1883, Annual Report, p. 4.)

In August 1883, the Surveyor General sought approval from the Crown Law Office to erect a standard of 66 and 100 feet in length. This was placed on 3 sandstone blocks along the North Quay frontage of the Supreme Court Building, Brisbane.

In 1885, the Chief Justice’s associate, J Harrison Byrne, wrote to the Surveyor General asking that the surveyors cease using this standard because its use:

‘... has begun to destroy his quiet and privacy which it was originally intended his chambers should have.’ (Queensland State Archives 1885, Letters SCT/89)

Responding to this request, the base standard was only used about a small number of times.

In November 1884, a new base for calibrating surveyors' tapes was laid down on the cement floor of the new survey office verandah in George Street Brisbane (on the site of the present Supreme Court). (Queensland Institute of Surveyors 1901, Transactions and Proceedings, vol. 1, p. 18.) It consisted of silver discs let into round copper plugs placed in the concrete floor at intervals of 30, 66, 100 and 110 feet. The problem with this base was the difficulty in determining the correct temperature of tapes resting flat on a concrete floor.

In 1896, Rockhampton District Surveyor CT Bedford established a standard of 500 links in Fitzroy Square, Rockhampton. This incorporated a 50 and 100 link and a 100 feet standard. (Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, 28 March 1896) The site and materials used to construct the base were donated by the Rockhampton Council. The base was marked by eleven concrete piers, fifty links apart and two and a half feet high. Bedford required the chain to be off the ground to record a true temperature of the chain:

‘When a standard was laid on the ground, the thermometer registered the heat of the ground and not necessarily the heat of the chain. By building piers, the chain when tested would be suspended in the atmosphere. Then by suspending the thermometer from a tripod placed close to the chain, a reading would be obtained which would accurately show the temperature of the chain - the thermometer and chain being suspended in the atmosphere under identical conditions.’ (Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, 28 March 1896)

By the 1890s, the Gunter's chain was replaced by the 5 chain band. In 1899, a base line comparator 5 chains in length was installed in the Brisbane Botanic Gardens. This allowed for tapes longer than 110 feet in length to be compared with each other. (Queensland State Archives 1899, Manuscript SUR/A99/1478)

In 1903, a new standard bar ordered from Troughton and Simms, London, arrived in Queensland. (Survey Office 1903, Annual Report, p. 81.) At the time, Great Britain and its dependencies were considering the adoption of a decimal system of weights and measures. As a result, there was 1, 2 and 3 metre lengths marked on the 10 foot bar which was already marked every 3 feet. This bar was never used due to a suitable site not being found for its installation. It is presently stored in the Museum of Lands Mapping and Surveying.

In 1910, metal plugs at 66 foot (100 links) and 82.5 foot (125 links) intervals were inserted in the concrete walkway on the north western side of the courtyard of the Executive Building in Brisbane (now the Conrad Treasury Hotel). This base was destroyed when the building was refurbished for the hotel in 1985.

In 1932, the Surveyor General of Queensland had a standard constructed in Stephens Lane on the south-eastern side of the Lands Administration Building, George Street, Brisbane. (Surveyor General 1932, Manuscript, file 19 part 1, Queensland State Archives) This base consisted of 3 concrete pillars with a wooden rail in between. Metal plugs were inserted into the tops of the pillars at intervals of 00, 66 and 100 feet distances. In 1940, an extra pillar at 50 feet was installed.

In 1950 Bill Newell, the officer in charge of tape standardisation reported on the problems he experienced while calibrating surveyors chains:

‘Besides being open to vandals, it must be admitted the site is not altogether satisfactory, one very serious drawback being the exposure to rain and sun rendering work impossible except in dry weather and afternoons. Though the Weights and Measures Department have not mentioned the following unpleasant conditions under which one sometimes has to work, a means of protecting employees from lighted cigarette butts, hot tea, or cold water thrown from the windows above should be considered. Although fortunately only minor burns have so far been inflicted, nevertheless the lodging of a lighted cigarette butt in one's hair or clothing might have more serious consequences. Furthermore, the smells from the drains in the vicinity at times are almost overpowering.’ (Newell, B 1950, Manuscript, Queensland State Archives)

In 1964, a new tape calibration bench was installed inside Morcom House, George Street, Brisbane.

Related links

- Learn about Queensland’s surveying history.

- View images of instruments and equipment used to survey and map Queensland.