Ecology

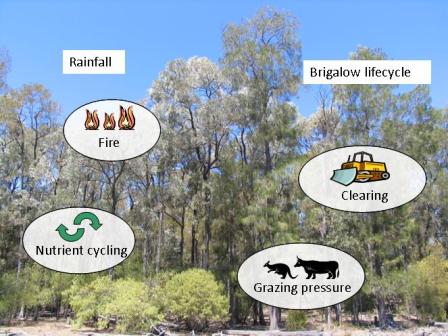

Understanding the ecology of brigalow vegetation helps us to manage and restore these systems for carbon and wildlife.

The biology of brigalow (Acacia harpophylla)

The brigalow tree is very productive in a relatively low-rainfall, high-evaporation environment. It can also tolerate high salt levels, even though growth will be slower under these conditions.

Brigalow has a well-developed horizontal root system, and plants are often joined together by these roots, forming colonies. A characteristic of brigalow is its ability to produce shoots from these horizontal roots (suckering) in response to disturbance.

More suckers are produced when:

- brigalow is damaged and soil moisture is low

- the stand is in a ‘sucker’ or ‘whipstick’ state (see below) from previous disturbance

- brigalow stems are rapidly destroyed (e.g. by lopping, chopping or pulling).

Fewer suckers are produced when:

- brigalow is damaged and soil moisture is high

- the stand is in a mature state (see sucker and whipstick brigalow below)

- trees are slowly killed (e.g. by ring barking or aerial herbicide spraying).

Fire can also cause suckering, although very hot fires may also cause severe damage to roots, and prevent regeneration. There is also some evidence that more suckers are produced following pulling and burning on deep ‘gilgaied’ clay soils.

Blade ploughing can be used to remove brigalow from a site as this destroys the lateral root system and this prevents suckering.

Reproduction and seedlings

Suckering is the main means of reproduction, as brigalow does not flower every year, and seed production is rare.

Brigalow seeds germinate rapidly once wet, and remain viable in soil for less than a year.

Seedlings will die if germination is not followed by good rains. As a result, it is unusual to find brigalow seedlings in natural landscapes, and revegetation of brigalow by direct seeding or planting tubestock is possible, but may be limited by the amount of seed produced, and its limited storage period (unlike many wattles).

Sucker and whipstick brigalow

If mature brigalow trees are removed from a site (e.g. by clearing), and many suckers are produced, brigalow can take the form known as ‘sucker brigalow’, where all brigalow plants have a low branching habit and are generally less than 4m in height.

Sucker brigalow may develop into another form of brigalow known as ‘whipstick brigalow’ after about 30 years. Whipstick brigalow typically consists of high densities of many straight, slender stems (4 to 8m tall) with spindly or dead lower branches.

The high densities of plants in sucker brigalow and whipstick brigalow cause strong competition for resources like water and light. This competition can affect the development of brigalow forest by slowing the growth of trees, and making it hard for other plant species to establish.

Clearing

The potential for brigalow to regrow after clearing is influenced by how it is cleared initially and how the land is used afterwards. Chaining or pulling brigalow vegetation often leaves living stumps and roots that will resprout if there is minimal disturbance (e.g. by hot fires).

When clearing is undertaken in this way, the species composition of the regrowth is strongly influenced by which species were present before clearing, and the diversity of plant species in older regrowth is similar to uncleared stands.

As a result, it is likely that brigalow that is left to regrow after chaining or pulling could eventually resemble mature stands of uncleared brigalow.

When brigalow stands are pulled (once or repeatedly), it seems that more intensive efforts are required to restore the original structure and plant species, compared to stands cleared by less severe means (e.g. ringbarking).

It is most difficult to restore brigalow if the original vegetation has been removed altogether (e.g. by blade ploughing and aerial herbicide spraying) and replaced by exotic grass species or crops. In this case, natural regeneration of brigalow vegetation will be unlikely without controlling weeds and replacing native vegetation (by planting tubestock, or direct seeding).

A mixed brigalow/gidgee woodland degraded by exotic grass invasion and subsequent fire in central Queensland.

Fire

Brigalow generally recovers from fire by suckering. Other plant species in brigalow forests can also survive fire and resprout.

However hot fires can kill trees and shrubs, prevent brigalow regeneration by causing severe damage to roots, and greatly alter the structure of brigalow vegetation.

Fires are usually rare in mature brigalow vegetation because there isn’t much fine fuel (e.g. leaf litter, or dry grass), although extreme fire weather or other unusual circumstances (e.g. fuel loads created by prickly pear eradication in the early 1930s) sometimes result in hot fires.

Fires in brigalow become more frequent and intense when exotic grasses invade or verge on remnant patches. More open stands of brigalow, such as patchy brigalow regrowth or brigalow woodlands in low rainfall areas, are more susceptible to grass invasion because of increased light.

The spread of exotic grasses, e.g. buffel grass, into brigalow patches can also be helped by thinning trees, disturbing soil, and moving livestock and vehicles.

With the exception of clearing, the most important threat to brigalow is fire fuelled by exotic grasses. Thus the control of grass fuel loads is an integral part of fire management in brigalow. Grazing, shading by trees and shrubs, herbicide control, low severity fires and even hand-pulling may be used to reduce grass fuel loads, and in this way reduce the number and frequency of wildfires.

Grazing pressure

Many trees and shrubs present in brigalow vegetation are eaten by stock, so grazing pressure can strongly affect these and other species.

Very high densities of sheep are a well-established method of controlling young brigalow suckers as sheep will eat the very young suckers until the plants turn green and ‘harden off’.

It is not uncommon to see distinct ‘browse lines’ in brigalow vegetation—the height of these reflects the reach of the dominant herbivore, and underneath there is very little foliage.

Grazing by high densities of black-striped wallabies can also prevent the establishment and growth of woody understorey species in remnant brigalow and vine thickets.

However, grazing by stock can also be a useful management tool for controlling exotic pasture grasses (and therefore fire risk) in brigalow vegetation. When bulky pasture grasses (e.g. buffel) are present, grazing may also increase the growth rates of brigalow by reducing the competition from grasses.

Nutrient cycling

Both brigalow and the often-associated belah (Casuarina cristata) can convert atmospheric nitrogen to a form that is available to other plants, and increase the amount of nitrogen and carbon in the soil (nutrient cycling).

Perhaps not surprisingly, the clearing of brigalow forests for pasture and cropping has been linked to declines in soil nitrogen and carbon. Productivity measures for grain and cattle also decline following a brief peak immediately after clearing. It is not known whether the restoration of brigalow vegetation in these areas will require, or benefit from, some kind of soil rehabilitation before native plants are replaced.

Dry rainforest or brigalow?

Brigalow can develop into dry rainforest (also known as semi-evergreen vine thicket or softwood scrub) if it gets enough moisture, is protected from fire, and has a suitable seed source.

If your site will support dry rainforest, it may be preferable to restore this vegetation type rather than ‘pure’ brigalow. Brigalow mixed with dry rainforest trees is likely to accumulate more carbon, and a shady dense tree and shrub layer will be more resistant to grass invasion and hot fires.