Greater bilby

Common name: Greater Bilby

Scientific name: Macrotis lagotis

Family: Thylacomyidae

Status: Endangered

As one of Queensland’s endangered mammals, the greater bilby is the subject of intense conservation efforts.

The greater bilby is the size of a rabbit and has a long, pointed nose, silky pale blue-grey upper body fur, big ears and a crested black-and-white tail. It measures up to 55cm in body length and its tail can be up to 29cm long. The large ears provide sharp hearing which is important, when combined with a well-developed sense of smell, because the greater bilby can’t see very well. These appealing animals keep their noses down when they run, which contributes to their unusual gait.

Threats and recovery actions

Introduced predators such as foxes and feral cats pose the most serious threat to the bilby, having eliminated them from most of their former range. Its closest relative, the lesser bilby, is extinct. For many years there were no records of greater bilbies in Queensland and there were fears the species was extinct in the state. However, in 1988, surveys found the bilby persisting in far western Queensland.

Other threats include habitat fragmentation and changed fire patterns.

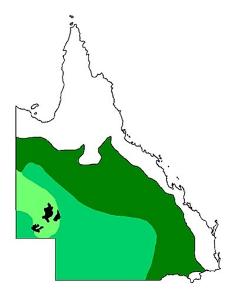

Today the greater bilby is found in several locations in western Queensland, with the largest remaining population in an area west of the Diamantina River, in Astrebla Downs National Park, Diamantina National Park and some adjacent pastoral properties.

In 2019, the greater bilby was re-introduced to a 2500-hectare predator-free enclosure in Currawinya National Park near the Queensland–New South Wales border. This highly successful project is thanks to a long-standing partnership between the Save the Bilby Fund and Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. This partnership also supports other recovery actions including a captive breeding program at Charleville.

Conserving the greater bilby in the wild requires habitat protection and extensive introduced predator control programs. An intensive recovery program has resulted in the bilby population at Astrebla Downs National Park climbing to 5000, with hundreds more at Currawinya National Park.

Ongoing research is conducted to better understand how greater bilby populations are changing over time and responding to management actions. This involves trialling different survey methods including aerial, ground and drone burrow surveys, and thermal image camera and spotlight surveys.

For more information about the greater bilby, view the species profile.

Learn more about how you can help the greater bilby and other Australian wildlife by supporting threatened species projects and caring for our native plants and animals.