Doomadgee

Introduction

Doomadgee is a largely Indigenous community located in the Gulf of Carpentaria, approximately 140km from the Northern Territory border and 93km west of Burketown. The community is positioned alongside the Nicholson River and provides access to the coast, freshwater rivers and Lawn Hill National Park, one of the Gulf’s most popular natural tourist attractions.

The Waanyi and Gangalidda people are recognised as the Traditional Owners for the region surrounding Doomadgee[1].

History of Doomadgee

European contact

The original mission, known as ‘Old Doomadgee’, was established in 1933 by a non-Indigenous family, the Akehurst family, with the support of the Christian Brethren Assemblies and Chief Protector of Aboriginals[2]. The mission was located at ‘Dumaji’ at Bayley Point Aboriginal reserve, on Gangalidda land[3].

The Akehursts lived in Burketown between 1930 and 1932, where they made contact with the Gangalidda and Garawa Aboriginal peoples and established a mission home for Aboriginal children. Many of the people who lived at ‘Old Doomadgee’ belonged to these groups[4].

The population at Old Doomadgee grew rapidly with the arrival of 10 Aboriginal boys and 10 Aboriginal girls from the Burketown mission in 1934. The boys were initially housed in tents, while the girls lived in a house previously occupied by the Akehursts[5]. The Protector of Aboriginals at Turn Off Lagoons also sent Aboriginal children and families to Old Doomadgee, some of whom belonged to the Waanyi people[6]. These removals appear to have been ‘unofficial’ and were not recorded in Queensland Government removal registers.

It is unclear when children at Old Doomadgee began living in dormitories, as few archival sources exist, but a diary kept by Vik Akehurst confirms the use of dormitories at both the Burketown and Doomadgee missions[7]. A photograph from the early 1930s shows a ‘boy’s house’ at Old Doomadgee that may have been the first boy’s dormitory. The hut resembles the log cabins described by the Akehursts that were built at the old mission in 1932[8].

A shortage of fresh water and other difficulties at Old Doomadgee led the Queensland Government to believe that the site was unsuitable for planned population expansions. When a cyclone largely destroyed the mission in 1936, the decision to relocate the mission took effect[9]. Around 50 children and 20 adults were living at Old Doomadgee just prior to relocation. The Chief Protector of Aboriginals vigorously supported the relocation despite local opposition, arguing it would facilitate ‘better control of the natives, and improve facilities for the employment of Aboriginal labour by landholders of the district’[10].

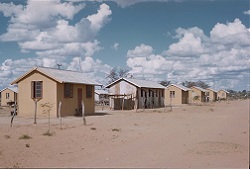

The new mission was established at the present site on the Nicholson River[11]. The site facilitated rapid population growth, particularly during the 1930s and 1940s, when the Queensland Government removed many Aboriginal families from surrounding pastoral stations including Westmoreland, Lawn Hills and Gregory Downs. ‘Official’ removals to Doomadgee totalled more than 80 between 1935 and 1957[12].

Prior to the establishment of Doomadgee, many Aboriginal children in the Gulf region were removed to the mission at Mornington Island and to other missions and reserves further south. Queensland Government records indicate that over 160 people were removed from Burketown between 1900 and 1974[13].

Archival records and personal accounts by residents describe the restrictive and difficult conditions at Doomadgee. In 1950, a government report severely criticised practices in use in the dormitory. At the time, mission policy required that all children over 6 years old lived in dormitories[14]. Boys left the dormitory around the age of 14 to take up station work. Girls were trained in domestic duties and often remained in the dormitories until they married[15].

By the late 1950s, many residents left Doomadgee and went to the Mornington Island mission, where the practice of separating children from parents in dormitories had been abandoned. During the 1960s, older, unmarried girls began returning to their parents[16]. The dormitories closed at some point in the late 1960s[17].

In 1969, the Queensland Government was appointed trustee of the reserve on which Doomadgee was located[18]. Continuing criticism of conditions at Doomadgee led the Queensland Government to assume administrative control from the Brethren in August 1983[19].

Local government and Deed of Grant in Trust community

On 30 March 1985, the Doomadgee community elected 5 councillors to constitute an autonomous Doomadgee Aboriginal Council[20]. On 21 May 1987, the Aboriginal reserve was transferred from the Queensland Government to the trusteeship of the Doomadgee Aboriginal Council, under a Deed of Grant in Trust (DOGIT)[21].

On 1 January 2005, the Doomadgee Aboriginal Council became the Doomadgee Aboriginal Shire Council.

End notes

- Lardil Peoples v Queensland [2004] FCA 298; Lardil, Yangkaal, Gangalidda & Kaiadilt Peoples v State of Queensland [2008] FCA 1855;Gangalidda and Garawa People v State of Queensland [2010] FCA 646.

- National Library of Australia, Vic Akehurst interviewed by Gwenda Davey in the Bringing them home oral history project [sound recording] (2001) https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-218411131/listen at 13 December 2012.

- Queensland, Queensland Government Gazette, 26 November 1938, 2128; Queensland, Queensland Government Gazette, 1917, 757; D Trigger, Whitefella Comin': Aboriginal Responses to Colonialism in Northern Australia (Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1992) 19; National Library of Australia, ‘Left Burketown, Les gained permission to establish reserve’ – Session 1 in Vic Akehurst interviewed by Gwenda Davey in the Bringing them home oral history project [sound recording] (2001) http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn2456344 at 13 December 2012.

- National Library of Australia, ‘Spreading gospels to Aboriginal people’ and ‘Living arrangements, establishment of dormitories’- Session 1 in Vic Akehurst interviewed by Gwenda Davey in the Bringing them home oral history project [sound recording] (2001) http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn2456344 at 13 December 2012.

- National Library of Australia, ‘Transportation of boys and girls, first arrivals to Doomadgee’ in Vic Akehurst interviewed by Gwenda Davey in the Bringing them home oral history project [sound recording] (2001) http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn2456344 at 13 December 2012.

- National Library of Australia, ‘Transportation of boys and girls, first arrivals to Doomadgee’ in Vic Akehurst interviewed by Gwenda Davey in the Bringing them home oral history project [sound recording] (2001) http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn2456344 at 13 December 2012; Trigger, above n 2, 63.

- National Library of Australia, ‘Transportation of boys and girls, first arrivals to Doomadgee’ in Vic Akehurst interviewed by Gwenda Davey in the Bringing them home oral history project [sound recording] (2001) http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn2456344 at 13 December 2012.

- Trigger, above n 3, plate 4 (photograph of ‘Boys house’); National Library of Australia, ‘Planning for establishment of reserve’ & ‘Arrival and contributions of Robert Gates in 1932’ - Session 1 in Vic Akehurst interviewed by Gwenda Davey in the Bringing them home oral history project [sound recording] (2001) http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn2456344 at 13 December 2012.

- National Library of Australia, ‘Len building wells for drinking water and associated problems’ in Vic Akehurst interviewed by Gwenda Davey in the Bringing them home oral history project [sound recording] (2001) http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn2456344 at 13 December 2012; trigger, above n 2, 57.

- Trigger, above n 3, 57.

- Queensland, Queensland Government Gazette, 7 November 1936, 1453; Queensland, Queensland Government Gazette, 29 November 1947, 1592; National Library of Australia, Vic Akehurst interviewed by Gwenda Davey in the Bringing them home oral history project [sound recording] (2001) http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn2456344 at 13 December 2012, (refers to Nicholson River site as old cattle station).

- Queensland, Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships, Community and Personal Histories Removal Database (the first official removal to Doomadgee occurred in 1935, the last in 1957). Access is restricted to this database.

- These people were removed to Deebing Creek, Barambah, Palm Island, Mornington Island, Mapoon, Fantome Island, Peel Island, Yarrabah and Woorabinda: Queensland, Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships, Community and Personal Histories Removal Database.

- The government report described Doomadgee as the ‘worst example of the ills of the dormitory system’, and referred to Doomadgee girls as being ‘most severely restrained’: Queensland State Archives, file 1D/133, memo dated 19.6.1950 from the Deputy Director of Native Affairs regarding Doomadgee Mission; see also Queensland, Annual Report of the Director of Native Affairs for 1950 (1951) 37; Queensland, Annual Report of the Director of Native Affairs for 1956 (1957) 35; Queensland, Annual Report of the Director of Native Affairs for 1958 (1959) 32; Queensland, Annual Report of the Director of Native Affairs for 1959 (1960) 32.

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1938 (1939) 20; Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1947 (1948) 30; Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1951 (1952) 36; Queensland, Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for 1958 (1959) 33.

- K Yearn, Doomadgee Aboriginal Mission System (Unpublished, University of Queensland, 2009) (primary sources quoted: J P M Long, ‘Aboriginal Settlements: A Survey of Institutional Communities in Eastern Australia in Aborigines’ (1970) 3, Australian Society Series 152; Trigger, above n 3, 70.

- Trigger, above n 3, 71.

- Queensland, Queensland Government Gazette, 29 November 1969, 1297.

- Queensland State Archives, SRS 3501/1, Item 24-034-003, Doomadgee, Finance, Auditor General's Report Doomadgee; Trigger, above n 2, 72.

- Queensland, Annual Report of Department of Community Services for 1986 (1987) 3; Queensland, Annual Report of Department of Community Services and Ethnic Affairs for 1988 (1989) 11.

- Queensland, Annual Report of the Department of Community Services for 1987 (1988).